Just a quick post because this is so cool, and the blog is the easiest way I have of sharing audio. I just bought iZotope RX3 to help with my auditions. All I have is a cheap (yet surprisingly good) Shure USB mic, a room with only so-so acoustics, and a neighborhood and appliances that provide a lot of background noise. I learned about the software because the engineer on my audiobook project uses it to process out the mouth clicks.

This is like science fiction, which is what Layer Paint looked like to me when I first saw it retouching images. Layer Paint? Oh, I'll have to tell that story in a later post. Let's just say that many of its features later showed up in a product called Photoshop.

This really is like Photoshop for sound. A total game changer. My serial number arrived just a few hours ago. I sat down and recorded this quick test, and then processed it a step at a time. What you will hear in this one minute sample is the same 15-second audio four ways:

- The raw audio. Note the background noise, mouth clicks, and iPhone chime.

- The Denoise feature has pretty much made the room noise vanish.

- DeCrackle has killed almost all the mouth clicks.

- I literally painted out the sound of the iPhone chime.

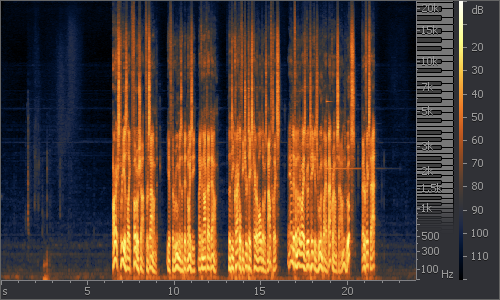

The UI displays the audio like this:

The blue is the waveform you're used to seeing. The yellow/red is the audio spectrum, with low frequencies at the bottom and high at the top.

See that horizontal streak in there? No? Oh, let me dial it over to show just the spectrum.

That iPhone text tone stands out as a horizontal stripe at one frequency.

The software has a time/frequency selection tool that let me draw a box around that horizontal stripe where the offending tone was. Then the Spectral Repair feature has a way to attenuate it. Really slick.

I'm not claiming this is polished audio at all. That's the point. I could have gone from the raw recording to the finished one in about five minutes. Without the offending text tone it would have been good to go in one minute.

Pretty cool. And a lot cheaper than hiring a studio or finding another house.